Altitude (triangle)

In geometry, an altitude of a triangle is a straight line through a vertex and perpendicular to (i.e. forming a right angle with) a line containing the base (the opposite side of the triangle). This line containing the opposite side is called the extended base of the altitude. The intersection between the extended base and the altitude is called the foot of the altitude. The length of the altitude, often simply called the altitude, is the distance between the base and the vertex. The process of drawing the altitude from the vertex to the foot is known as dropping the altitude of that vertex. It is a special case of orthogonal projection.

Altitudes can be used to compute the area of a triangle: one half of the product of an altitude's length and its base's length equals the triangle's area. Thus the longest altitude is perpendicular to the shortest side of the triangle. The altitudes are also related to the sides of the triangle through the trigonometric functions.

In an isosceles triangle (a triangle with two congruent sides), the altitude having the incongruent side as its base will have the midpoint of that side as its foot. Also the altitude having the incongruent side as its base will form the angle bisector of the vertex.

In a right triangle, the altitude with the hypotenuse as base divides the hypotenuse into two lengths p and q. If we denote the length of the altitude by h, we then have the relation

.

.

Contents |

The orthocenter

The three altitudes intersect in a single point, called the orthocenter of the triangle. The orthocenter lies inside the triangle (and consequently the feet of the altitudes all fall on the triangle) if and only if the triangle is not obtuse (i.e. does not have an angle greater than a right angle). See also orthocentric system.

The orthocenter, along with the centroid, circumcenter and center of the nine-point circle all lie on a single line, known as the Euler line. The center of the nine-point circle lies at the midpoint between the orthocenter and the circumcenter, and the distance between the centroid and the circumcenter is half that between the centroid and the orthocenter.

Unlike the centroid and circumcenter of a triangle, the orthocenter has no special characteristics (such as being equidistant from all sides or vertices).

The isogonal conjugate and also the complement of the orthocenter is the circumcenter.

Four points in the plane such that one of them is the orthocenter of the triangle formed by the other three are called an orthocentric system or orthocentric quadrangle.

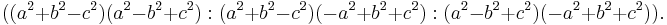

Let A, B, C denote the angles of the reference triangle, and let a = |BC|, b = |CA|, c = |AB| be the sidelengths. The orthocenter has trilinear coordinates sec A : sec B : sec C and barycentric coordinates

Orthic triangle

If the triangle ABC is oblique (not right-angled), the points of intersection of the altitudes with the sides of the triangles form another triangle, A'B'C', called the orthic triangle or altitude triangle. It is the pedal triangle of the orthocenter of the original triangle. Also, the incenter (that is, the center for the inscribed circle) of the orthic triangle is the orthocenter of the original triangle.[1]

The orthic triangle is closely related to the tangential triangle, constructed as follows: let LA be the line tangent to the circumcircle of triangle ABC at vertex A, and define LB and LC analogously. Let A" = LB ∩ LC, B" = LC ∩ LA, C" = LC ∩ LA. The tangential triangle, A"B"C", is homothetic to the orthic triangle.

The orthic triangle provides the solution to Fagnano's problem which in 1775 asked for the minimum perimeter triangle inscribed in a given acute-angle triangle.

The orthic triangle of an acute triangle gives a triangular light route.[2]

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the orthic triangle are given by

- A' = 0 : sec B : sec C

- B' = sec A : 0 : sec C

- C' = sec A : sec B : 0

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the tangential triangle are given by

- A" = −a : b : c

- B" = a : −b : c

- C" = a : b : −c

Some additional altitude theorems

Equilateral triangle theorem

For any point P within an equilateral triangle, the sum of the perpendiculars to the three sides is equal to the altitude of the triangle.

Inradius theorems

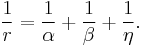

Consider an arbitrary triangle with sides a, b, c and with corresponding altitudes α, β, η. The altitudes and incircle radius r are related by

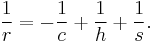

Let c, h, s be the sides of 3 squares associated with the right triangle; the square on the hypotenuse, and the triangle's 2 inscribed squares respectively. The sides of these squares (c>h>s) and the incircle radius r are related by a similar formula:

The symphonic theorem[3]

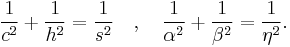

In the case of the right triangle, the sides of the 3 squares c, h, s are related to each other by the symphonic theorem, as are the 3 altitudes α, β, η. The symphonic theorem states that triples (c2,h2,s2) and (α2,β2,η2) are harmonic, and that triples  and

and  are Pythagorean:

are Pythagorean:

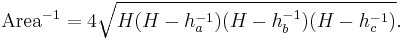

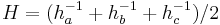

Area theorem

Denoting the altitudes from sides a, b, and c respectively as  ,

,  , and

, and  ,and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as

,and denoting the semi-sum of the reciprocals of the altitudes as  we have[4]

we have[4]

In-line references

- ^ William H. Barker, Roger Howe (2007). "§ VI.2: The classical coincidences". Continuous symmetry: from Euclid to Klein. American Mathematical Society Bookstore. p. 292. ISBN 0-8218-3900-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=NIxExnr2EjYC&pg=PA292. See also: Corollary 5.5, p. 318.

- ^ Bryant, V., and Bradley, H., "Triangular Light Routes," Mathematical Gazette 82, July 1998, 298-299.

- ^ Price, H. Lee and Bernhart, Frank R. (2007). "Pythagorean Triples and a New Pythagorean Theorem". arXiv:0701554.

- ^ Mitchell, Douglas W., "A Heron-type formula for the reciprocal area of a triangle," Mathematical Gazette 89, November 2005, 494.

See also

References

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Altitude" from MathWorld.

External links

- Orthocenter of a triangle With interactive animation

- Animated demonstration of orthocenter construction Compass and straightedge.

- An interactive Java applet for the orthocenter

- Fagnano's Problem by Jay Warendorff, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.